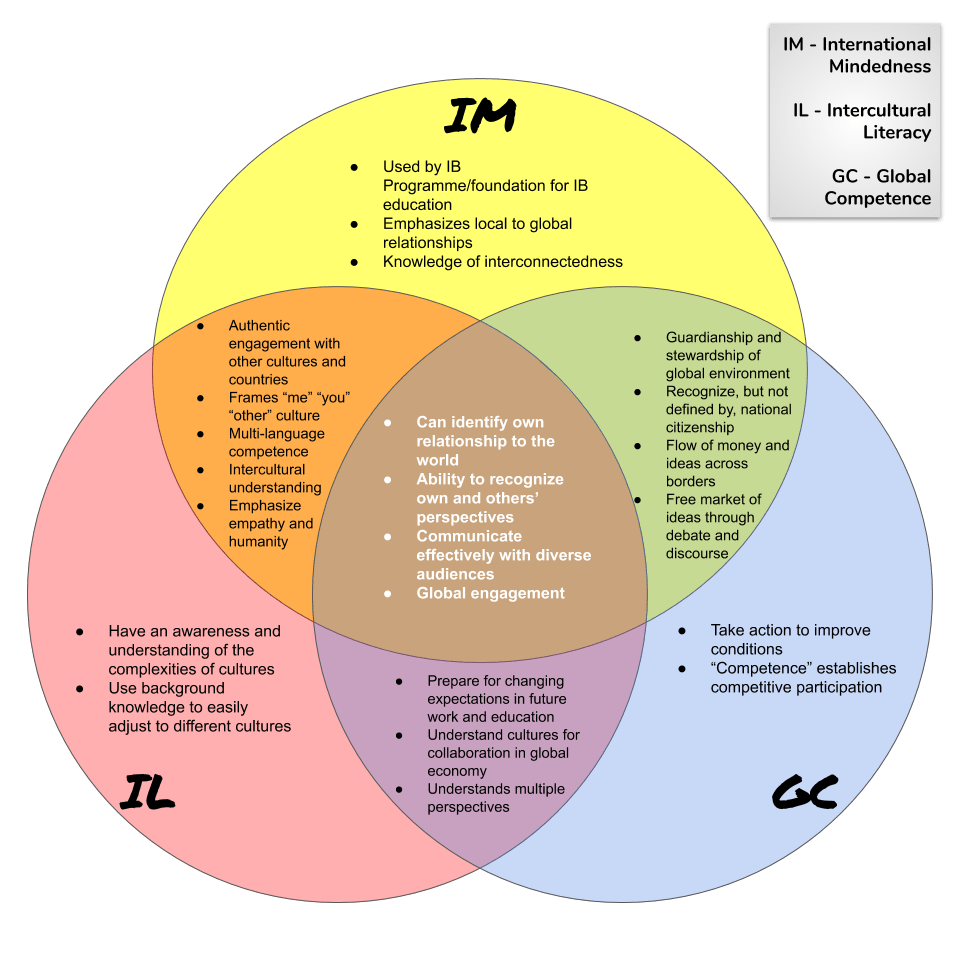

International schools are preparing the students of today for the world of tomorrow. To do this, the schools are navigating flowing, dynamic currents that are sometimes dissonant and sometimes harmonious. The students and their families are globally mobile citizens bringing their own cultures into the melting pot of the school – a culture all its own – before moving on to other countries and cultures. Schools are operating in the present global space, but preparing students for a future that is expected to be even more closely connected and interdependent across national boundaries and societies. International schools are therefore juggling the current needs of their perpetually changing student body with their students’ anticipated needs for happy, fulfilling lives in the future. With the lofty goal of preparing their students for active participation in the global world, these schools must teach international mindedness, intercultural literacy, and global competence to some degree and hopefully in harmonious balance. The Venn diagram above highlights similar aspects of these, illuminating shared values in the global 21st century.

On first reading these three terms may sound quite similar, almost synonymous, but in fact there are subtle and overt differences. International mindedness seeks to develop students into global citizens who are members of their own national heritage, but also citizens of the world with responsibility to both national and international interests. These include responsible stewardship of the local environment and the planet, multilingualism for international communication, and deep knowledge of world history and people. All this is toward the greater good of ensuring world peace and cooperation. Unfortunately, this framework still reinforces an “us” and “them” construct. Everyone is expected to stay in their lane and do the appropriate or expected amount of learning and outreach to connect with other people from other countries. This presupposes that everyone has the resources and opportunities for an (expensive) international education with the same understanding and orientation toward these goals. There is criticism that international mindedness perpetuates a global elite operating in their own international space while everyone else in lower classes are left behind (Sriprakash et al., 2014).

Intercultural literacy shares the goal of connecting people from all over the world, but focuses more on culture and humanity than on national boundaries or political constructs. Students who gain intercultural literacy are prepared to communicate in several languages as well as read the needs of other people and empathize with their situation. These students adapt to new places and cultures by diving in, participating, engaging with, and reflecting on daily experiences (Heyward, 2002). Whereas international mindedness could be interpreted as competitive, intercultural literacy is cooperative. With cooperation, inclusion, and empathy, the interculturally literate respond to dynamic, changing environments with an understanding that not one size fits all.

Global competence shares similarities with both intercultural literacy and international mindedness, yet is still a unique conception. This framework focuses on preparing students for work life and economic considerations in the global world of tomorrow. Many of the same skills are helpful and beneficial here insomuch as they strengthen active participation in solving global problems. More than the other two, global competence equips students to proactively identify, assess, and solve large-scale problems of the world. This requires understanding of other cultures to leverage cooperation and resources toward transnational issues, smoothing the way for cross-border exchanges of money and ideas (Mansilla & Jackson, 2012). Transactions of the most innovative ideas, valuable resources, and best products sets up nations for successful, competitive participation in the world economy. Once again, we revisit competition, an under-the-radar aspect of international mindedness, but an overt pillar of global competence. In fact, competition is right there in the name of the framework.

As you can see in the diagram above, all three efforts prepare students to understand their own relationship to the world around them, not simply their individual role in a national frame as a citizen or worker. This shared space between international mindedness, intercultural literacy, and global competence is perhaps the most important of all. Global citizens must be able to evaluate their own perspectives as well as other perspectives. This is true today and will be true tomorrow. The imperative to communicate effectively with diverse audiences of people different from oneself is present in these three constructs and is indeed a major objective of international schools. None of these would be possible without global engagement and each one accomplishes this in its own way. It would be advisable for schools to focus on these shared strengths as there must be great value in those similarities. Each framework, with differing and sometimes overlapping goals, finds camaraderie here.

References

Drake, B. (2004). International Education and IB Programmes. Journal of Research in International Education, 3(2), 189-205. doi:10.1177/1475240904044387

Heyward, M. (2002). From international to intercultural: Redefining the international school for a globalized world. Journal of Research in International Education, 1(1), 9-32. doi:10.1177/1475240902001001266

Mansilla, Veronica & Jackson, Anthony. (2012). Educating for Global Competence, Preparing our Youth to Engage the World. doi:10.13140/2.1.3845.1529.

Sriprakash, A., Singh, M., & Qi, J. (2014). A Comparative Study of International Mindedness in the IB Diploma Programme in Australia, China and India. Retrieved from http://www.ibo.org/globalassets/publications/ib-research/dp/international-mindedness-final-report.pdf

Van Oord, L. (2007). To westernize the nations? An analysis of the International Baccalaureate’s philosophy of education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 37(3), 375-390. doi:10.1080/03057640701546680